This pages is meant to be a place to share a few of the books that I have read, what they look like, and what stood out to me about them. There's almost certainly going to be spoilers here, so I do apologize in advance.

Reviews of Books I don't own- King Solomon's Ring

- Sucker's Progress: An Informal History Of Gambling in America From the Colonies to Canfield

- Gulliver's Travels

- Mortal Engines and Fiasco

- Puck of Pook's Hill

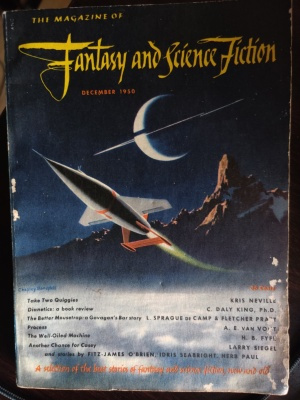

- Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction: Vol. 1 No. 5, December 1950

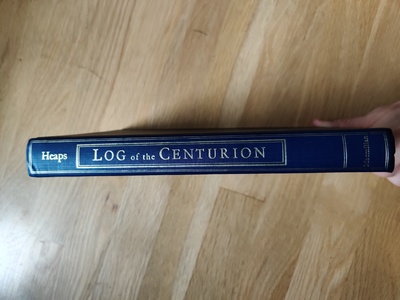

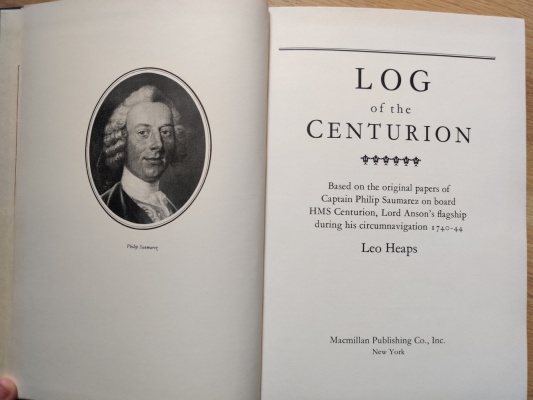

- Log of the Centurion

- A Wizard of Earthsea

- Snow Crash

- Vathek

Author: Konrad Z. Lorenz

Translation: Marjorie Kerr Wilson

First Read: 2024/10/20

Drawing parallels with the mythical ring of King Solomon which grants the ability to converse with animals, Lorenz achieves the same feat by watching and cavorting with animals of all varieties with an mind boggling amount of patience and compassion. This book, written casually out of experiences the author had raising a variety of creatures in varying states of domesticity-- geese, fish, songbirds, dogs, shrews, jackdaws in his family's home in Altenburg, Germany during in the 1930s.

Lorenz recounts countless little anecdotes of animal behavior and his own eccentric behavior in trying to make his meaning known to them. I found myself openly laughing on a train as I read about his attempts to bring his cockatoo home by making loud bird sounds at the creature in the middle of the train station or ran from his band of jackdaws by leaping around the roof in a devil costume. Lorenz's experiments in pond aquariums and wild animal rearing are sufficiently detailed to invite replication for anyone who is not afraid of the chaos wrought by animals allowed to be themselves.

...I had gone only a few steps along the street and the crowd had not yet dispersed when, high above me in the air, I saw a bird whose species I could not at first determine. It flew with the slow, measured wing-beats, varied at set intervals by longer periods of gliding. It seemed too heavy to be a buzzard; for a stork, it was not big enough and, even at that height, neck and feet should have been visible. Then the bird gave a sudden swerve so that the setting sun shone for a second full on the underside of the great wings which lit up like stars in the blue of the sky. The bird was white. By Heaven it was my cockatoo! The steady movements of his wings clearly indicated that he was setting out on a long-distance flight. What should I do? Should I call to the bird? Well, have you ever heard the flight-call of the greater yellow-crested cockatoo? No? But you have probably heard pig-killing after the old method. Imagine pig squealing at its most voluminous, taken up by a microphone and magnified many times by a good loudspeaker. A man can imitate it quite successfully, though somewhat feebly by bellowing at the top of his voice "O-ah". I had already proved that the cockatoo understood this imitation and promptly "came to heel". But would it work at such a height? A bird always has a great difficulty making the decision to fly downwards at a steep angle. To yell or not to yell, that was the question. If I yelled and the bird came down, all would be well, but what if it sailed calmly on through the clouds? How would I then explain my song to the crowd of people? Finally, I did yell. The people around me stood still, rooted to the spot. The bird hesitated for a moment on outstretched wings, then, folding them , it descended in one dive and landed upon my outstretched arm. Once again I was master of the situation...

Throughout the chapters of the book, delightful illustrations in the marginalia express the language that the subject animals use as much as the remarkable character of Lorenz himself. I feel like there was a short period of time in the middle of the 20th century where these sorts of doodles could be found in any book. I'd love to see it come back in fashion again. It adds to the light-hearted character of the book while being illustrative of the animal anatomy and behavior discussed.

...In birds, even in parrots, of which the opposite if often maintained, there is no law of attraction of opposites, by which female animals are drawn towards men and males toward women. [A] tame adult male jackdaw fell in love with me and treated me exactly as a female of his own kind. By the hour, this bird tried to make me creep into the nesting cavity of his choice, a few inches in width, and in just the same way a tame male house sparrow tried to entice me into my own waistcoat pocket. The male jackdaw became most importunate in that he continually wanted to feed me with what he considered to be the choicest of delicacies. Remarkably enough, he recognized the human mouth in an anatomically correct way as the orifice of ingestion and he was overjoyed if I opened my lips to him, uttering at the same time an adequate begging note. This must be considered as an act of self-sacrifice on my part, since even I cannot pretend to like the taste of finely minced worm, generously mixed with jackdaw saliva. You will understand that I found it difficult to co-operate with the bird in this manner every few minutes! But if I did not, I had to guard my ears against him, otherwise, before I knew what was happening, the passage of one of these organs would be filled, right up to the rum with warm worm pulp, for jackdaws, when feeding their mate or their young, push the food mass, with the aid of their tongue, deep down into the partner's pharynx...

Written in 1949, following Lorenz's service as a drafted Nazi psychologist and field medic at a Soviet PoW camp, the narrative has hints of melancholy recollection for both the animals that he lost and the outlook of humanity. The stories seem to sparkle like a lost eden as he meanders along trails that now look permanently altered by the conflict. One wants to imagine the world could return to the whacky antics of greylag geese and curious jackdaws but of course nature itself has its seeming cruelties. While he saves much of the moral philosophizing to other books, there's still a touch of it in the uncertain and ominous conclusion of Solomon's Ring.

My familiarity with the modern study of ethology is limited to popular science books (such as Honeybee Democracy, which was deeply inspired by Lorenz's contemporary Karl von Frisch) so it's unclear to me how much of the hypothesizing in Solomon's Ring has held up over the years. Given the book focuses on personal experiences and stories rather than rigorous scientific experimentation, it's hard to fault any of the light conclusions made within. Concepts like imprinting are touched upon, but were expounded more formally by Lorenz in scientific literature. The real aim of the book is to serve as inspiration to others, "[a] small 'up-current' which might lift some other scientist to a point from which [they] could see a little further than I do". And if the number of scientific institutions bearing his name, (and the number of copies of this book I've found squirreled away in used book stores) is any indication, that was certainly achieved.

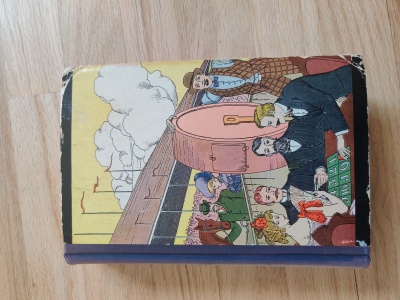

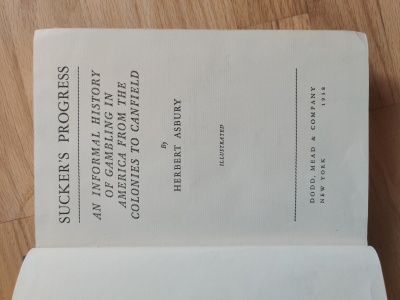

Author: Herbert Asbury

First Read: 2021/11/25

I love a good informal history, but I also find watered down historical summaries to be pointless. Thus, this book, being deeply researched and full of delightful first-hand stories, is among one of my favorite books to come from the Nevada County Historical Society book sale.

Containing both an explanation of the rules of play of many games now out of fashion as well the history of gaming in the major American cities of the 18th and 19th centuries, this book takes one back to a time before Vegas or mobsters. Perhaps of note was how simply ubiquitous cheating by the house was. Even with games like faro or craps which are mathematically in favor of the dealer, deception played a major part of gambling up until the late nineteenth century. Though, I suppose it's somewhat common knowledge. It's the irrationality of gambling as well as my distaste for loud noises and binging on buffet food that has generally kept me clear of casinos. Nonetheless, this book provides the picturesque view-- card games on steam boats, smoke-clouded parlor games of gentlemen, and the exploits of fairground hucksters.

Despite the relatively light and unbiased dealing of the material, Asbury doesn't hold back ond describing gambling-related ruin, lynchings (indeed the origin of the term), and squalor. At no point does gambling appear to be a sound investment for anyone except the crooked.

I'm most grateful to this book for turning me on to Wanderings of a Vagabond and Poker Stories which provide extensive contemporary accounts of gambling as well as pictures of working class society in the nineteenth century. Wanderings of a Vagabond in particular is an absolute pleasure to read. The author's tangents or as informative as his memoir is engaging. One day maybe I'll find a hard copy of it...

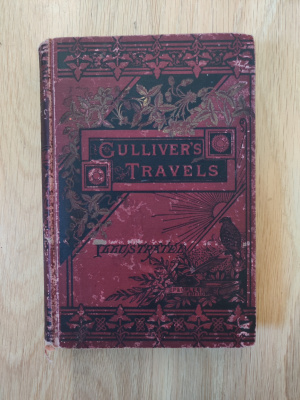

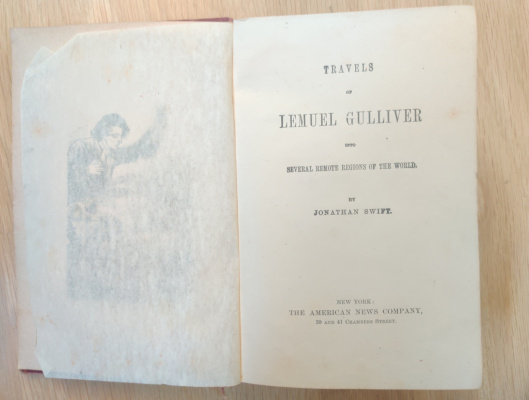

Author: Jonathan Swift

First Read: 2021/01/15

Despite the nearly 300 years that separate its authorship and my first reading of it, Gulliver's Tavels remains not only readable to the average reader, but fascinating. It's one of the few books that my father has ever read. While my early attempts at reading the book in elementary school proved too challenging due to the dated verbiage, it's this very feature that captivated me as an adult. Now that I had a sufficient grasp on history (plus a copy of Wiktionary close by), I was able to take in the novel as one takes in Shakespeare in their first real reading of his works.

The scenes in Lilliput and Laputa have a dream-like creativity that is hard to find outside of fantasy RPGs and surrealist art. I wished the descriptions of the learnings of the Balnibarbian scientists lasted many more pages. The novel's influence on pop culture and technology are unmistakable. That being said, despite my enjoyment of the British History podcast and all the drama it describes, I found myself apathetic to some of the satiric raves the book hosts. But it's more absurd than extracting sunbeams from cucumbers than to expect all of the gripes of pre-industrial novel to remain relevant so much later.

The trip to Glubbdubdrib inspired me to create a tiny little role-playing game encounter.

the party disembarks from their ship and follows a cobblestone path through a verdant garden of neat hedges and trimmed trees. Along the way they encounter a standing corpse. It's attired as a gardener, mouth agape, missing an arm and trying to use their remaining arm and chest to get the hedge trimmer to close on a branch. If the party talks to them, they say that they have been summoned from the dead for 24 hours by the necromancer who rules the land. When asked by the party how they like the arrangement, they say through a disintegrating jaw that it isn't so bad. Their nerves have all died so they feel no pain and it's curious to see how the world has changed since they were last awoken. The one downside being their body decays in the grave so they never get any prettier. Seeing as the party is headed toward the castle, they ask the party to wish his/her greatgrandnephew the necromancer well.I've found it rare to be able to travel along with an author's description of an adventure as well as I was able to follow Swift's narration. The great entertainment provided by the magical sights almost undermines the gravity of Gulliver's trip to the land of the Houyhnhnms. Finally, I'm not going to lie-- I really wish there were more pictures in the book. A single print in the beginning of a book does not count as illustrated, American News Company!

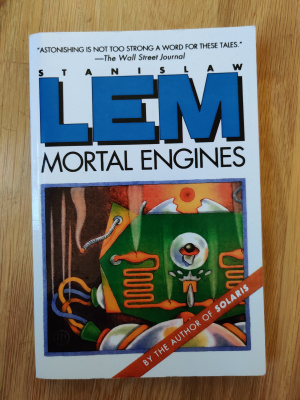

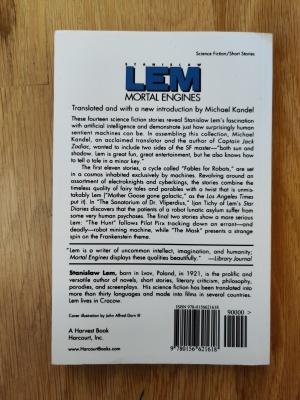

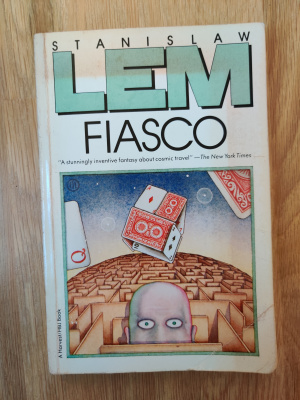

Author: Stanislav Lem

First Read: 2019/06/15, 2020/09/07

My first run in with Stanislav Lem was through the Tarkovsky film Solaris (1972). Like any Tarkovsky film, it's stunning. However, it doesn't really match the tone that I would later learn Lem was famous for-- humor. While on a search for Summa Technologiae, his non-fiction work on computers and philosophy, I found a few of his fiction works and figured I'd give them a shot. I'm a sucker for Harcourt covers.

Mortal Engines (1964) is a magical set of short stories: imaginative alien realms, alternative chemistries, and retellings of medieval narratives on other planets. Despite the humor and whimsy of the tales, they get a wee hard to get through after five or six in a row. Thus, "The Hunt" really shakes up the fantasy dimension with a human-centered story of man vs rogue robot. The setting is immaculate, tickling my love of desolate civilian space stations and space truckers. Here's the first two paragraghs (more like pages):

He left Port Control hopping mad. It had to happen to him, to him! The owner didn't have the shipment-- simply didn't have it-- period. Port Control knew nothing. Sure, there had been a telegram: 72 HOUR DELAY-- STIPULATED PENALTY PAID TO YOUR ACCOUNT--ENSTRAND. Not a word more. At the trade councillor's office he didn't get anywhere either. The port was crowded and the stipulated penalty didn't satisfy Control. Parking fee, demurrage, yes, but wouldn't it be best if you, Mr. Navigator, lifted off like a good fellow and went into hold? Just kill the engines no expenditure for fuel, wait out your three days and come back.What would that hurt you? Three days circling the Moon because the owner screws up! Pirx was at a loss for a reply, but then remembered the treaty. Well, when he trotted out the norms established by the labor union for exposure in space, they started backing down. In fact, this was not the Year of the Quiet Sun. Radiation levels were not negligible. So he would have to maneuver, keep behind the Moon, play that game of hide-and-seek with the Sun using thrust; and who was going to pay for this? --not the owner, certainly. Who then-- Control? Did you gentlemen have any idea of the cost of ten minutes full burn with reactor of seventy million kilowatts? In the end he got permission to stay, but only for seventy-two hours plus four to load that wretched freight-- not a minute more! You have thought they were doing him a favor. As if it were his fault. And he had arrived right on the dot, and didn't come straight from Mars either-- while the owner...

With all this he completely forgot where he was and pushed the door handle so hard on his way out, that he jumped up to the ceiling. Embarrassed, he looked around, but no one was there. All Luna seemed empty. True, the big work was under way a few hundred kilometers to the north, between Hypatia and Toricelli. The engineers and technicians, who a month ago were all over the place here, had already left for the construction site. The UN's great project, Luna 2, drew more and more people form Earth. "At least this time there won't be any trouble getting a room," he thought, taking the escalator to the bottom floor of the underground city. The fluorescent lamps produced a cold daylight. Every second one was off. Economizing! Pushing aside a glass door, he entered a small lobby. They had rooms, all right! All the rooms you wanted. He left his suitcase, it was really more a satchel, with the porter, and wondered if Tyndall made sure that the mechanics reground the central nozzle. Ever since Mars the thing had been behaving like a damned medieval cannon! He really ought to see to it himself , the proprietor's eye and all that... But he didn't feel like taking the elevator back up those twelve flights, and anyway by now they had probably split up. Sitting in the airport store, most likely, listening to the latest recordings. He walked, not really knowing where; the hotel restaurant was empty, as if closed-- but there behind the lunch counter sat a redhead, reading a book . Or had she fallen asleep over it? Because here cigarette was turning into a long cylinder of ash on the marble top... Pirx took a seat, reset his watch to local time and suddenly it became late: ten at night. And on board, why, only a few minutes before, it had been noon. This eternal whirl with sudden jumps in time was just as fatiguing as in the beginning when he was first learning to fly. He ate his lunch, now turned into supper, washing it down with seltzer, which seemed warmer than the soup. The waiter, down in the mouth and drowsy like a true lunatic, added up the bill wrong, and not in his own favor, a bad sign. Pirx advised him to take a vacation on Earth, and left quietly, so as not to waken the sleeping counter girl. He got the key from the porter and rode up to his room. He hadn't looked at the plate yet and felt strange when he saw the number: 173. The same room he had stayed in, long ago, when for the first time he flew "that side." But after opening the door he concluded that either this was a different room or they had remodeled it radically. No, he must have been mistaken, that other was larger. He turned on all the switches, for he was sick of darkness, looked in the dresser, pulled out the drawer of the small writing table, but didn't bother to unpack, he only threw his pajamas on the bed, and set the toothbrush and toothpaste on the sink. He washed his hands-- the water, as always infernally cold, it was a wonder it didn't freeze. He turned the hot water spigot-- a few drops trickled out. He went to the phone to call the desk, but changed his mind, there was really no point. It was scandalous, of course-- here the moon was stocked with all the necessities , and you still couldn't get hot water in your hotel room! He tried the radio. The evening wrap-up-- the lunar news. He hardly listened, wondering whether he shouldn't send a telegram to the owner. Reverse the charges, of course. But no, that wouldn't accomplish anything. These were no the romantic days of astronautics! They were long gone, now a man was nothing but a truck driver, dependent on those who loaded cargo on his ship! Cargo, insurance, demurrage... The radio was muttering something. Hold on-- what was that?...

The plot after that could have been anything and I wouldn't have minded with those first few pages. This story is part of the Pirx the Pilot series which which brings me to the next book.

Fiasco (1986) is the final novel Lem wrote and features Pirx heavily. The first third of the book feels quite similar to "The Hunt" in which Pirx departs on a dangerous chivalric quest. As thrilled as I was to find more of this series, the novel takes a drastic turn toward a standoff between humans and an intelligent alien race discovered on a distant planet. Perhaps it's alluding to the politics of the Cold War, but it becomes a truly hard science fiction novel which I really wasn't looking for. Still fascinating and well written, just a lot more military and much less civilian oriented than I hoped.

I still have an unread copy of Memoirs Found in a Bathtub laying around here, but I've been a bit put off by the premise of bureaucracy as the main enemy. I believe that comes from the sense that bureaucracy was sort of the dystopia of the 20th century (much like the government landscape in Snow Crash). In my 21st century outlook, the future looks much more like Minority Report. That being said, Lem's writing is so captivating (even through the translation) that I'm able to enjoy it even if it doesn't hit like it might have in the 1960's.

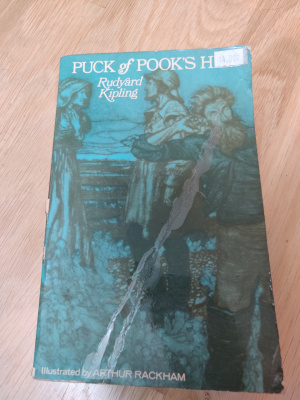

Author: Rudyard Kipling

First Read: 2020/07/08

I'd spent years scouring used book stores for a copy of this work of mythological fiction. I'd seen its pagan elements compared to The Wind in the Willows and with the way that I have loved The Golden Bough and The Wake, I was certain I would love this collection of stories of English folklore and history. This copy of Puck of Pook's Hill comes from deep in the stacks of White Rabbit Books in Muncie, Indiana and at a whopping price of $4. Which I suppose makes sense, it's illustrations aren't nearly as neat as the original's.

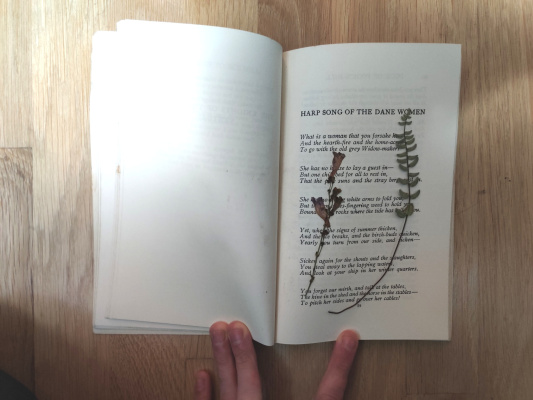

It was on a hiking trip to Tahoe (hence the pressed flowers) that I first opened up the book and I was enraptured by the Shakespearean play put on by the child protagonists in the first chapter. The book reads much like Alice in Wonderland with a child audience in mind and a somewhat storyteller narrative style with characters emerging from the wood to share their tales with the children. Each story is separated from the next with a little song or poem that feels much older than they are. Here's "A Tree Song":

Of all the trees that grow so fair,

Old England to adorn,

Greater are none beneath the Sun,

Than Oak, and Ash, and Thorn.

Sing Oak, and Ash, and Thorn, good sirs,

(All of a Midsummer morn!)

Surely we sing no little thing,

In Oak, and Ash, and Thorn!

Oak of the Clay lived many a day,

Or ever AEneas began.

Ash of the Loam was a lady at home,

When Brut was an outlaw man.

Thorn of the Down saw New Troy Town

(From which was London born);

Witness hereby the ancientry

Of Oak, and Ash, and Thorn!

Yew that is old in churchyard-mould,

He breedeth a mighty bow.

Alder for shoes do wise men choose,

And beech for cups also.

But when ye have killed, and your bowl is spilled,

And your shoes are clean outworn,

Back ye must speed for all that ye need,

To Oak, and Ash, and Thorn!

Ellum she hateth mankind, and waiteth

Till every gust be laid,

To drop a limb on the head of him

That anyway trusts her shade:

But whether a lad be sober or sad,

Or mellow with ale from the horn,

He will take no wrong when he lieth along

'Neath Oak, and Ash, and Thorn!

Oh, do not tell the Priest our plight,

Or he would call it a sin;

But - we have been out in the woods all night,

A-conjuring Summer in!

And we bring you news by word of mouth-

Good news for cattle and corn-

Now is the Sun come up from the South,

With Oak, and Ash, and Thorn!

Sing Oak, and Ash, and Thorn, good sirs

(All of a Midsummer morn):

England shall bide ti11 Judgment Tide,

By Oak, and Ash, and Thorn!

This ditty follows an excerpt about Wayland Smith which, though toned down for a child audience, is true to the core of the legend. The following story touches on a post-Hastings romance before taking a dire turn south. I'd known Kipling had a very imperialist mindset, having tried and failed to get through some of his works about India but "The Joyous Venture" really broke the spell that had been captivating me. In this, the knight from the previous story is captured by pirates and goes on a trip down to the African Gold Coast where caricatures of natives flea in terror from a rampaging pack of gorillas. I haven't gotten to read Equatorial Africa and the Country of the Dwarves yet, but being that it's the first time a gorilla is described by European writers, I imagine it carries much of the same prejudices. Perhaps I'm being unfair given the age this set of stories was written in (1906), but they certainly don't hold up well in a society where we treat folks of African descent as humans rather than specimens.

That being said, Puck of Pook's Hill is still lovely and eloquently written. Being an avid listener of The British History Podcast, I can't help but enjoy the overlap in events and subject matter. Furthermore, "A Centurion of the Thirtieth" seems to be a surprisingly accurate (at least given the little archaeological certainly there is) historical tale of the Roman occupation of England. Good going, Kipling, I suppose you can at least make a wonderful story out of some stone foundations and centuries of speculation.

I've certainly got mixed feelings about the book. Despite its cultural significance in England, I'm probably not going to be reading this to my children. But that's mostly because I'm not English.

Author: Various

First Read: 2020/11/08

I got a stack of mid-century editions of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (started in 1949) as a surprise from my mother for my birthday. Little does she know, I already have a huge back catalog of vintage science paperbacks in my bedroom. What typically draws me to science fiction from this era is that it still has that optimistic, galactic-manifest-destiny feel which is a nice break from the crushing reality of the Fermi Paradox.

That being said, the literature from this time period often needs to be taken with some understanding that it came from a different time (much like Kipling-- see review of Puck of Pooks Hill). This magazine contains a Fitz-James O'Brien story "The Wondersmith" that's a horrible charicature of Roma peoples and a plot from a B-movie. I simply can't imagine the reasoning of building this kind ofracist fear-mongering into fiction. But, ignoring that, other stories are a bit more amusing. There's a whacky alien story that is a quite thinly veiled diatribe against rampant consumerism, a story told from the perspective of an animate forest, and a lovely little psychological piece by Margaret St. Clair.

But I suppose the real reason I'm typing out this review for a piece of pulp is that it contains a review of L. Ron Hubbard's Dianetics which was published that year. I found the scathing review incredibly amusing since even at it's inception Scientology was clearly a sham. Even the editors politely shit on Hubbard's nonsense. Having visited the L. Ron Hubbard museum in Los Angeles out of curiosity, I was fascinated how a pulp author could turn into a weird cult leader with such ease. I think C. Daly King concludes my feelings well with:

It may be that dianetics is a therapeutic art, either valid or invalid; in which case let it admit that its conclusions can never be more than plausible or implausible opinions. Of a certainty, no number of Western Electric diagrams of the conceptual elements of subjective speculation can make it genuinely scientific

Nowadays we'd sum that up with the term vaporware. Science fiction from this era certainly doesn't ring with the humor of Rucker or the poignancy of Lem, but I hoping one of these times I'll find a book with a true lost gem of an era that had some hope for galactic exploration and intelligent extraterrestrial life.

Author: Captain Philip Saumarez (compiled by

Leo Heaps)

First Read: 2019/10/24

I found my copy of The Log of the Centurion in the world history section of The Bookery in Placerville, California. I had been on the lookout for old travel books, in a similar vein as The Travels of Marco Polo or The Travels of Sir John Mandeville when I happened upon this book about the HMS Centurion. I'd never heard of the Centurion, though by the end of the book I realized it had been on quite an incredible adventure.

Reading the tribulations of rounding Cape Horn, I recalled Irving Johnson's film Around Cape Horn which I happened to find on VHS at a junk shop a few months before beginning the Log of the Centurion. A bit of the film can be found on YouTube. Irving's carefree descriptions of the gymnastics the sailors performed to keep the SS Peking afloat are incredible.

As for The Log of the Centurion, the book is incredibly engaging. Despite the formal, descriptive nature of the ship's log, Heaps manages to provide enough context around the entries to make the book as engaging as any novel. The ship made surprise raids on the Spanish settlements in Peru even as the rest of the squadron was barely seaworthy. The legend of the ship climaxes with the capture of the Manila treasure galleons that had absolute naval superiority. Then, with a skeleton crew, Anson lead the ship across the Pacific to Macau and took his place in naval history. Even as someone who didn't grow up around sailors or naval history, I find the story incredible.

Much like other old travel/exploration books I've read (such as West African Explorers which included the diaries of Mungo Park), The Log of the Centurion contains bits of that mysterious world that hadn't been fully studied by the West. There are biases and imperfect information that make that time feel exceedingly more magical than today.

Books still on my list to read:

- Equatorial Africa and Country of the Dwarves - Owned, contains the first description of gorillas by a European

- The Golden Rhinoceras - A look at medieval African trade and civilization

- The Travels of Sir John Mandeville - An outlandish story of a trip to Near East

- Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems - An Arabic account of the beginning of time up through the Abbasid Caliphate written by a medieval Baghdadi historian

Anyway I spent weeks drawing tall ships in my sketchbook. I'm still working on a model of the Cutty Sark, but if anyone knows of an HMS Centurion model kit out there, I'd love to see it.

If anyone can point me to a copy of any of those books above, I'd be very appreciative!

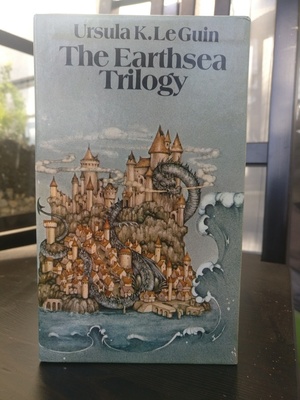

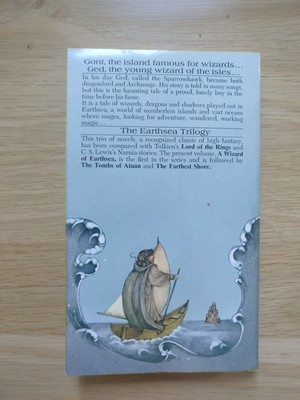

Author: Ursula K. Le Guin

First Read: 2019/03/24

The Earthsea Trilogy came to me too late in life. I had only heard about it well after I'd exceeded the age of its stoic protagonist. However, once I was a few pages into the book, I realized it was the sort of fantasy novel I had always wanted. Nearly all of my previous experience with the genre: short-stories, comics, and 80s paper-backs falling apart in my hands, was disappointing. Earthsea defied the expectation of shallow, superhero-style story telling by building humanized characters in a fantastic, but tempered world. The tropes of the hero's journey are built into unique settings that feel just as visceral in the 21st century as I'm sure they did in the middle of the 20th.

My girlfriend was the one who, upon spotting the original boxed-set of the Earthsea trilogy at Pegasus Books, went ahead and bought it for me. Because the books, though lemon-colored on the edges by age, are in immaculate condition, I've been in the habit of carrying the book around in a brown paper bag in my backpack and trying my best not to hurt the spine as I looked at the many illustrations of the map of Earthsea.

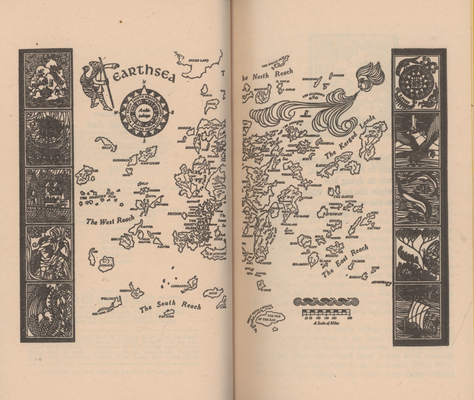

The map is essential to the stories of Earthsea. The maps, especially those in A Wizard of Earthsea are phenomenal works of art by Ruth Robbins. It sets the scene for the genuine, timeless fantasy novel. Being obsessed from childhood with maps and geography, I took breaks between chapters to draw my own worlds in the same manner. I won't share those here, but I will share the detail maps of the book which I scanned in and combined into one large map.

Vector files:

- earthsea_fullmap.svg -- the detail maps of the various islands stitched together into one map

- earthsea_fullmapfancy.svg -- the detail maps of the various islands stitched together into one map but with the cool graphics from the main, two-page map

- earthseaillustrations.zip -- chapter head illustrations + vector images

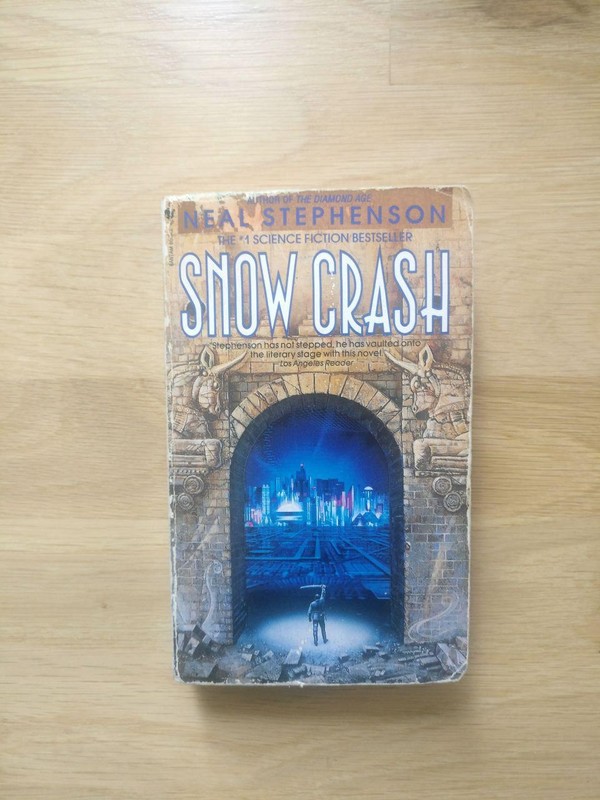

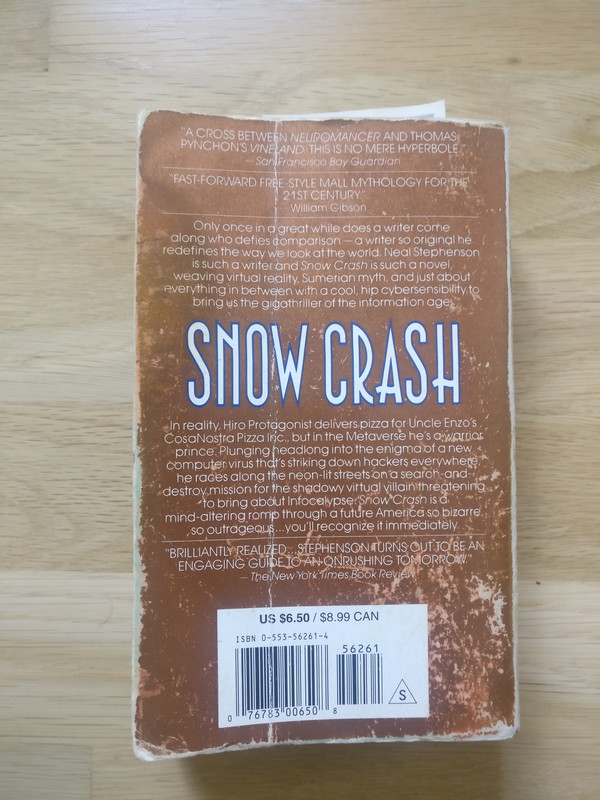

Author: Neil Stephenson

First Read: 2019/03/16

Snow Crash is one of those novels I'd been hearing about for years before actually cracking open. Once I began reading it, nearly all of my coworkers were eager to reminisce fondly over how it had influenced them. Perhaps comparable only to Neuromancer or Hitchhiker's, Snow Crash seems to be a piece of fiction that has become revered by nerds of the tech boom.

I found this particular copy well-worn in a book store in Santa Cruz, I believe and it sat on my shelf for well-over a year until I was sufficiently burnt out on non-fiction and wanted something to read on the train in the mornings before my brain starts working. I had only read Stephenson's non-fiction before, but more than one of my friends have entire shelves dedicated to his vast output of fantasy and science fiction.

My reading of Snow Crash started off pretty rough. The thick stream of metaphors and similes were a bit overwhelming:

The Deliverator's car has enough potential energy to blast a pound of bacon into the Asteroid Belt.or

...knowing more about pizza than a Bedouin knows about sand.But I think it was calling the Deliverator Hiro Protagonist that I finally clicked into the tongue-in-cheek narrative style that Snow Crash is written in. I was soon pretty engaged with Stephenson's predictions of the Internet and the hacker-vs-carrier dynamic. I found myself skimming past the fight scenes, but thoroughly engrossed in Stephenson's environment-and-character-building. Hiro comes off a bit like the Star Wars Kid and I kind of enjoy the way Stephenson pokes fun at hackers by calling those who are jacked in while interacting in the real-world 'gargoyles.'

The main premise of the novel is pretty far out. Sumerians and a giant floating evangelical revival was certainly not what I expected during the exposition of post-modern L.A. It's clear that Stephenson got into The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind while building out the new shape of America as a patchwork of corporate factions. The highlight of the book is the Metaverse. It's the easiest thing to point to and relate to the world of 2019. It has the idealistic hacker aesthetic of the 1990s where the coders can be independent and unique while the masses have to abide by the rules of the program and rely on off-the-shelf avatars. This is an alternate reality which doesn't have the oligarchy of social networks that have bought out the best real estate and where the best hackers haven't dedicated their lives to making more invasive ads.

Simultaneously, the novel has a few details that are ironically missing in modern society. YT gets a mouthful of bugs. I can't help but think there used to be more bugs in the cities, but it might just be some New York Times brainwashing. The sterile and stringent office culture for corporate and federal programmers has been replaced, at least in most of the tech sector in 2019, by open offices overflowing with benefits. Yet, it's often a trade-in of one's personal life for these riches. Only the bravest, sharpest, most cringeworthiest of us can strike out against the Man.

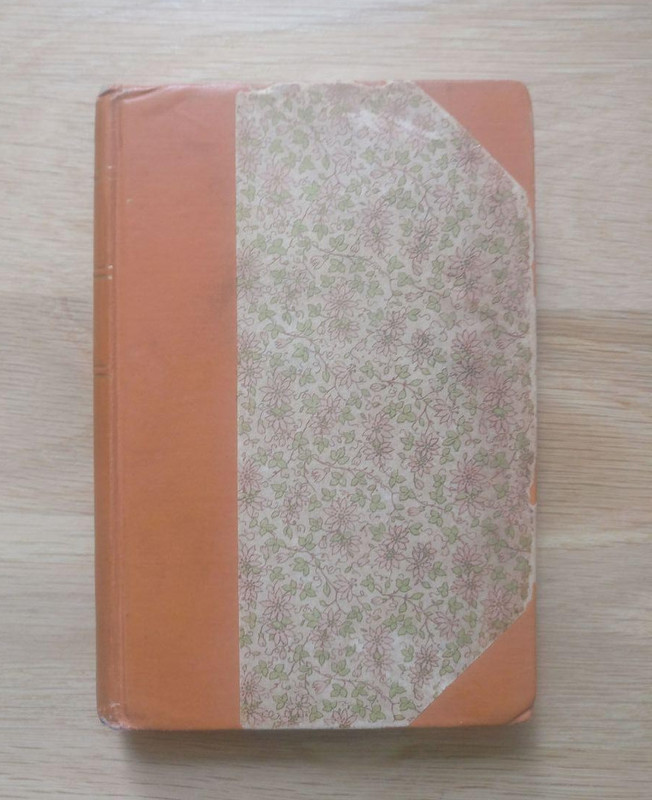

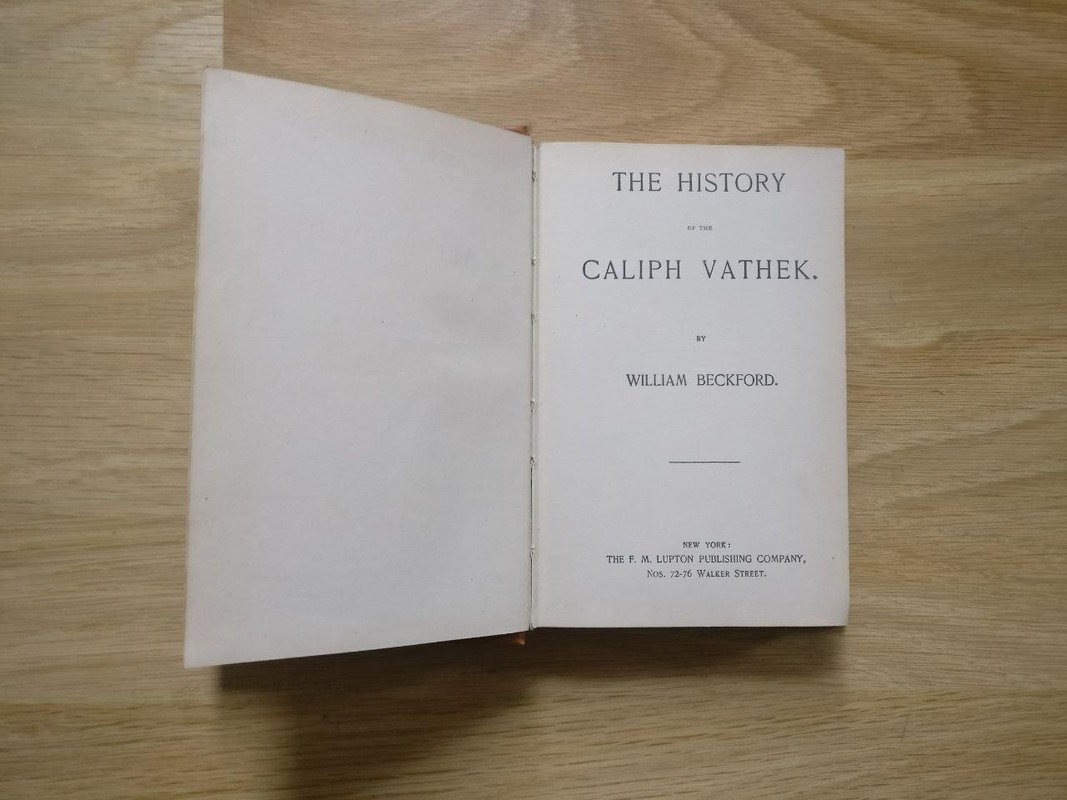

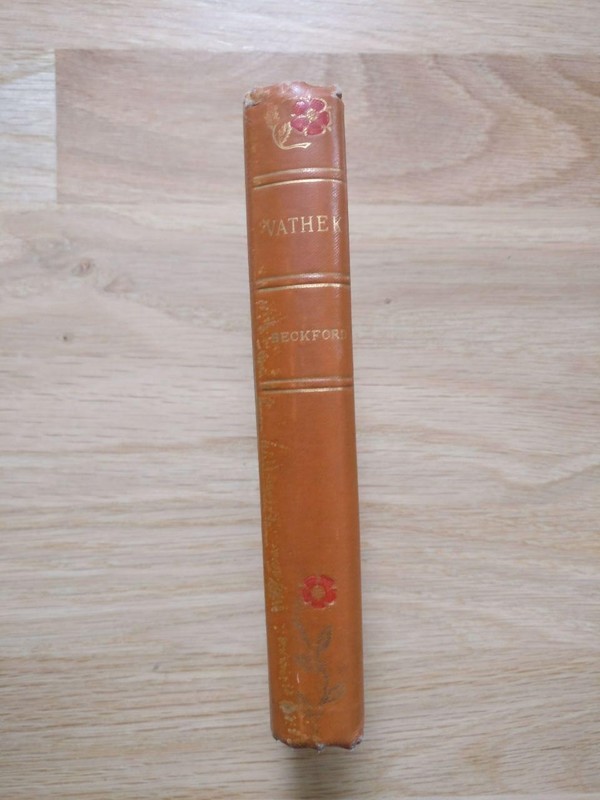

Author:: William Beckford

First Read: 2019/03/29

When I first picked out Vathek from the ever-interesting Miscellaneous shelf at B Street Books in San Mateo, California, I thought it was a first-hand history of an 18th century ruler. Vathek is actually a gothic and arabesque fiction from 1786 that had profound influence on later authors of dark fiction/fantasy. No complaints here.

This copy of Vathek is cloth-bound with a gilt top and gilt lettering with some quaint floral patterns on the spine and covers. The floral patterns are probably a bit silly given the content of the novel, but hey, it's a pretty book and I'm sure Victorian were into it.

The plate reveals that it is a reprint by F.M. Lupton Publishing Co. (later Federal Book Company). By the address of Nos. 72-76 Walker Street, New York, this book would have been published some time during the years 1894-1899 according to this Henry Altemus site and, taking a guess based on appearance, falls into the Souvenir Series. It seems 1894 is a good date to put on this book's printing.

Vathek isn't a light read, nor is it particularly straightforward, even for someone pretty acquainted with the flowery language of gothic authors. However, Beckford creates marvelous and grotesque images as he drives on his idiotic and doomed antihero. The peasants of the eponymous ruler's kingdom are often just ants, annihilated to justify Vathek's fate:

In the paroxysm of his passion, [Vathek] fell furiously on the poor carcasses [of his soldiers], and kicked them till [sic] evening without intermission.

[Vathek and his retinue] passed through two villages almost deserted, the only inhabitants remaining being a few feeble old men, who, at the sight of the horses and litters, fell upon their knees and cried out: "O Heaven! is it then by these phantoms that we have been for six moths tormented? Alas! it was from the terror of these spectres and noise beneath the mountains, that our people have fled, and left us at the mercy of maleficent spirits!" The Caliph, to whom these complaints were but unpromising auguries, drove over the bodies of these wretched old men...Not a super nice dude. However Vathek is mostly a puppet of his mother who pretty much sets up all of the black magic and gives him not-so-gentle pushes to get off his ass and commit some atrocities in the name of the Dark Lord. And thus Vathek plays out, massacre after massacre until the Vathek meets the devil and realizes that he made a terrible mistake by trusting the ruler of the Underworld.

As a modern reader, I find the ending of Vathek unsatisfying. Along with the miraculous salvation of the innocents of the story by the benevolent spirits, the destruction of Vathek's powerful mother even as she stares the devil in the face comes off as a cop-out to appease the literary requirement of Good's triumph over Evil. Regardless, I found the novel substantially more graphic than anything I had ever read by Poe or Lovecraft. Vathek ranks up with 120 Days of Sodom for most fucked up things done in a book, but the tale of Vathek is immensely more enjoyable. Faust and Vathek share a similar fantasy journey to the limits of human comprehension before being smashed to the ground by their inevitable mortality. In my pursuit of knowledge, I hope that I don't miss such obvious signs that I have gone down the wrong path.